Branded types to avoid human errors

10 min read

If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.

Typescript differs from other typed languages such as Java or C# in that it is a structural type system. This means that two types are considered equal if they have the same structure. This can lead to some problems, especially when working with primitive types. For example, the following code will compile without any errors:

// User class with a userId property

class User {

constructor(public userId: string) {}

}

// Function to validate a User object

declare function validateUser(user:User) : boolean

// instance of User class

const user = new User('1')

// it gives no errors.

validateUser(user)

// User object with a userId property - we are not using the User class here

const user2 = {userId: '1', name: 'John Doe'}

// it gives no errors.

validateUser(user2)The above code will compile without any errors even though the user2 object is not really an instance of the User class. This means Typescript is happy with as long as any object has a shape of User class. You may have noticed that the user2 object has an extra property name which is not present in the User class, Typescript does not really care about it. This can be understood better by considering Typescript types as set.

Typescript types and Sets have too much in common

When we use mathematical sets as a way to think about types, everything makes sense how Typescript is the way it is. A set is a collection of distinct objects, considered as an object in its own right. In the same way, a type in Typescript is a set of values. For example, the type number is a set of all numbers, the type string is a set of all strings, and so on. When we define a type in Typescript, we are defining a set of values that a variable can take.

I would stretch further to say that Typescript is a purely functional language, where everything is a set, i.e. it operates over types in a purely functional paradigm of programming. This is why it is so easy to reason about types in Typescript using sets, especially in more complex types like union types, intersection types, and so on.

Example:

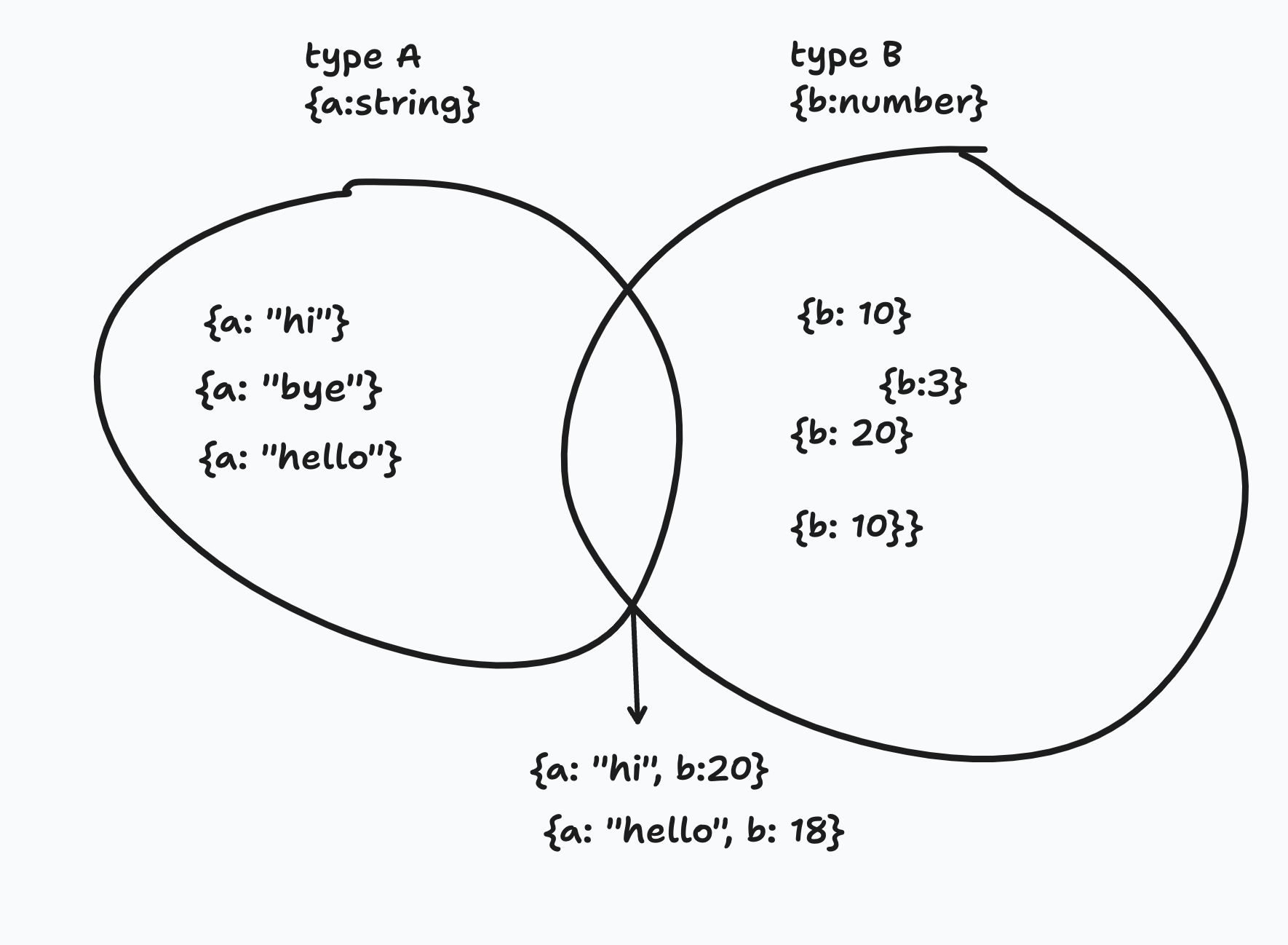

type A = {a: string}

type B = {b: number}When we do intersection of two types, A & B, intiutively we may think, they have nothing in common in terms of the properties as both A and B seem mutually exclusive with A and B no overlapping properties. But in terms of sets, the intersection of two sets is the set of all elements that are in both sets. So the intersection of types A and B is a set containing properties from both A and B, i.e. {a: string, b: number}. This can be understood with diagram below.

Ais a set of all the objects that have a propertyaof typestring. That means anything that has atleast one propertyaof typestringis part of the setA.- Similary,

Bis a set of all the objects that have a propertybof typenumber. That means anything that has atleast one propertybof typenumberis part of the setB. - Intersection of both

AandBis the set of all the objects that have both propertiesaof typestringandbof typenumber. It goes against our intuition that intersection of two types with no common properties should be an empty type.

Similarly:

type A = {a: string}

type B = {a: string}

type C = {a: string, b: number}

function f(x: A) {

return x

}Three of the above types A, B, and C are equivalent because they have the same structure. Because if we think of type A as a set of all the objects that have a property a of type string, then type B is the same set as type A. This is because they have the same structure. The type C is a different set because it has an extra property b of type number. However it is also part of the set of type A because it has the property a of type string.

Please note that Types are not 1 to 1 mapping to sets, but it is a good way to think about them. And in the function f, if we pass an inline object with extra property other than a, it will not give any error because it is part of the set of type A.

This behaviour is intentional

Typescript is designed this way to make it easier to work with Javascript. Javascript is a dynamically typed language, which means that the type of a variable is determined at runtime. This can lead to some unexpected behaviour, especially when working with objects. As your engineering spirit would say: it is a feature, not a bug.

For example, when working with remote data repositories, you may not always know the structure of the data you are working with, i.e. it could have excessive properties which you are not concerned about and in that case, Typescript’s structural type system is a blessing. It allows you to work with data without having to worry about its structure. As long as the data has the properties you are interested in, Typescript is happy, and so are you.

Branded types to the rescue

type UserId = string

type SessionId: stringSuppose you are working on a multi tenant application where you have to deal with multiple user ids and session ids. Due to structural typings, you can easily mix up user ids with session ids.

function isUserLoggedIn(userId: UserId, sessionId: SessionId) {

// some logic

}

// we accidentally got the order wrong

isUserLoggedIn(session.id, user.id)As you can see, it is very easy to mix up user ids with session ids. This can lead to some serious bugs, it can take you whole morning on a very beautiful sunny day to debug this. This happened because both UserId and SessionId are just strings, and Typescript had no other information other than both types being strings. So how do we go further? Well, Typescripts want more information, and that’s exactly what we are do, give it more info, more metadata about the types.

Branded types

It is very easy to create branded types in Typescript. A branded type is a type that is a subset of another type. For example, we can create a branded type UserId that is a subset of the string type. This means that a UserId is a string, but not all strings are UserIds. We can do this by using a unique symbol as a brand in the type definition.

- we will create a generic type to generate branded types.

// /brand.type.ts

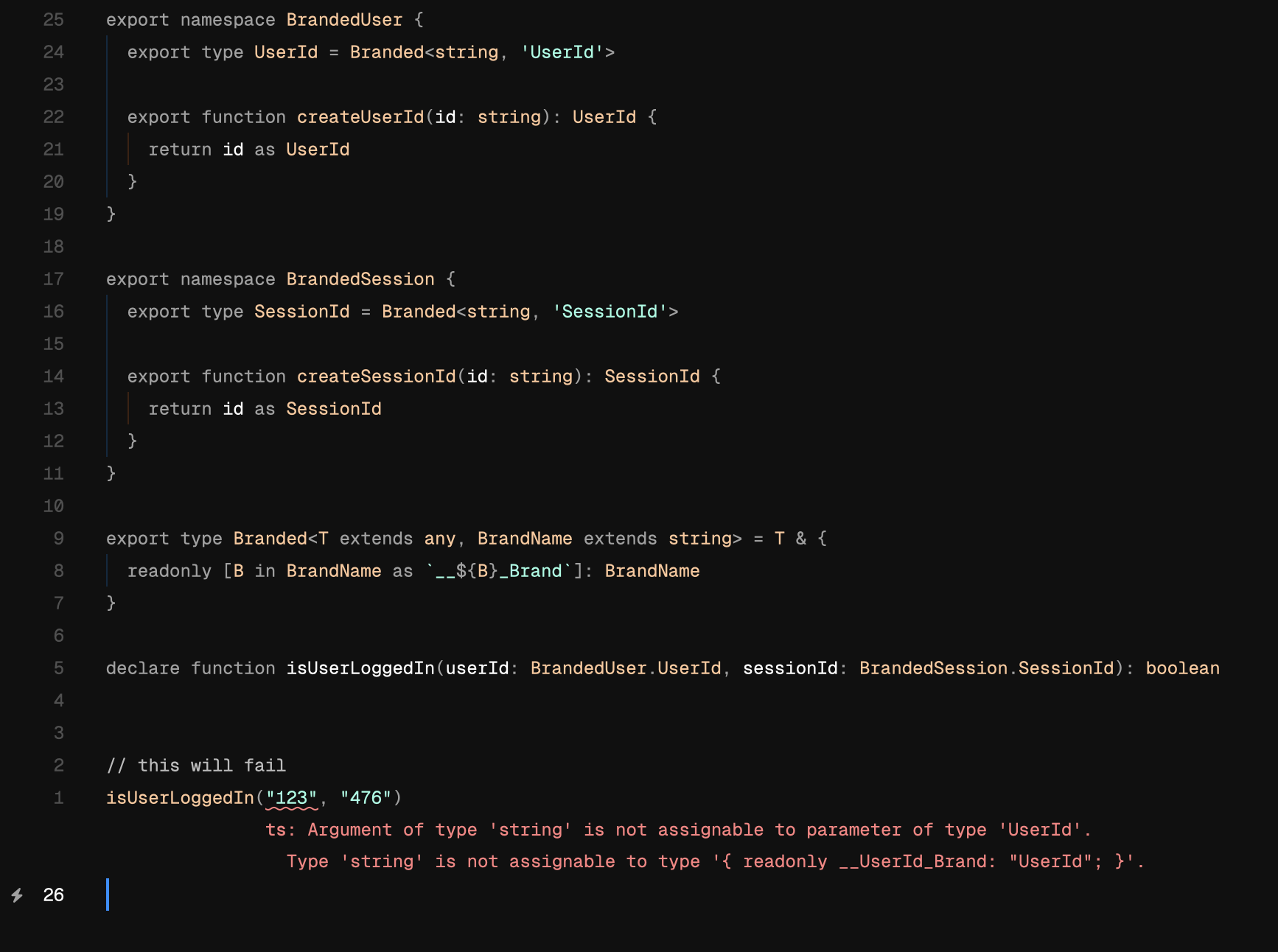

export type Branded<T extends any, BrandName extends string> = T & {

readonly [B in BrandName as `__${B}_Brand`]: BrandName

}-

The above example has a generic type called

Brandedthat takes two generic params:T- the type that we want to brandBrandName- the name of the brand We create an intersection of the typeTand an object with a unique symbol as a brand. The brand is a readonly property with the name of the brand. This ensures that the brand is unique and cannot be changed.

-

We will create Typescript namespaces called

BrandedUserandBrandedSessionto hold our types and utilities to work with branded types. Typescript namespaces are a way to organize your code and prevent naming conflicts. I use them a lot because of how narrow my brain is, when it comes to naming things. We will use the namespace to hold our branded types and utilities to work with them.

export namespace BrandedUser {

export type UserId = Branded<string, 'UserId'>

export function createUserId(id: string): UserId {

return id as UserId

}

}

export namespace BrandedSession {

export type SessionId = Branded<string, 'SessionId'>

export function createSessionId(id: string): SessionId {

return id as SessionId

}

}-

The

UserIdtype is a branded type that is a subset of thestringtype. We use theBrandedtype to create a branded type calledUserId. TheUserIdtype is a string, but not all strings areUserIds. We also create a utility function calledcreateUserIdthat takes a string and returns aUserId. This function is used to create aUserIdfrom a string. -

This may seem like a lot of work for nothing, but it is worth it. Suppose the function

isUserLoggedInnow takes aUserIdand aSessionIdinstead of astring. This means that we cannot mix upUserIds withSessionIds anymore.

import {BrandedUser, BrandedSession} from './brand.type'

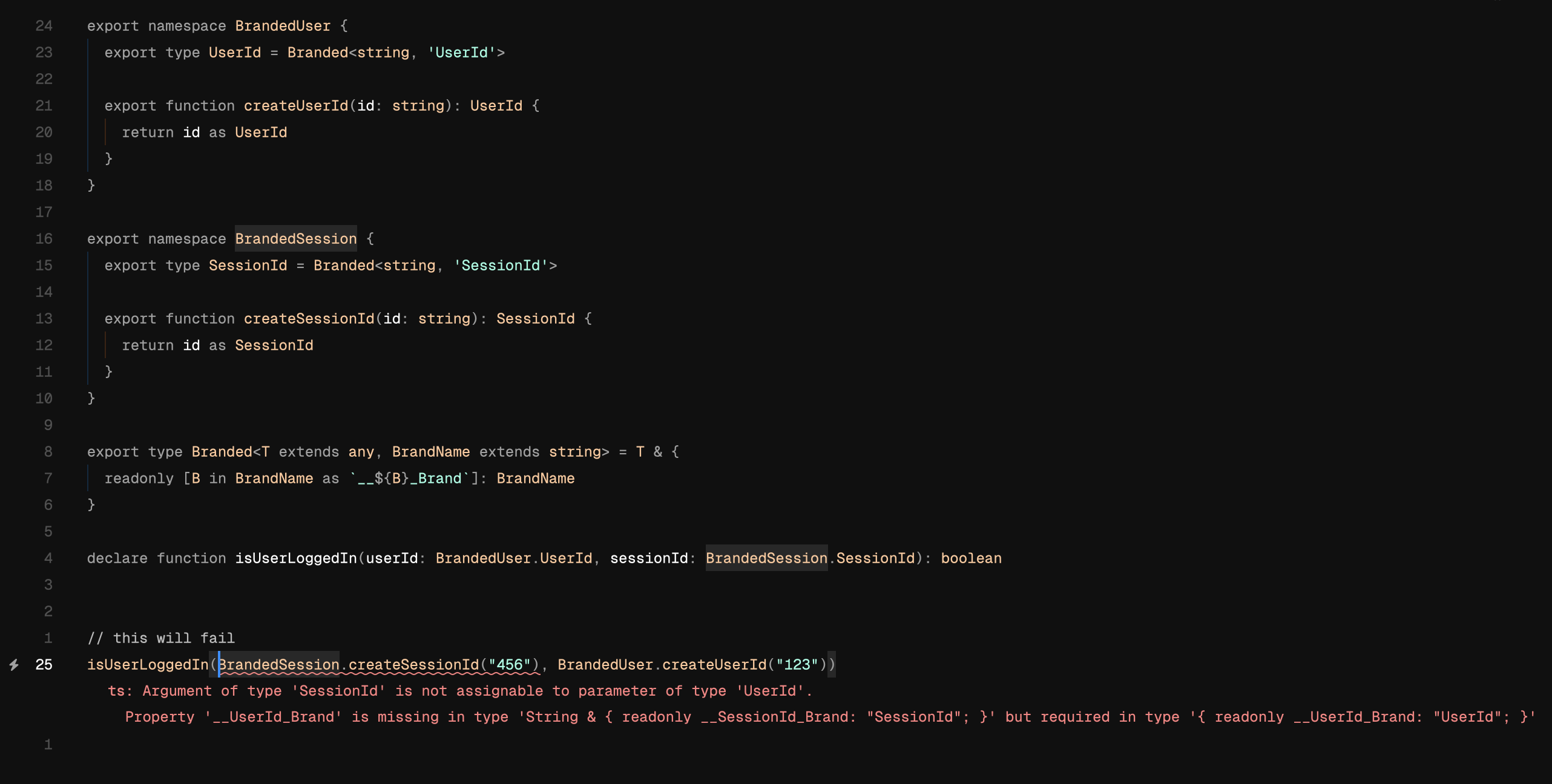

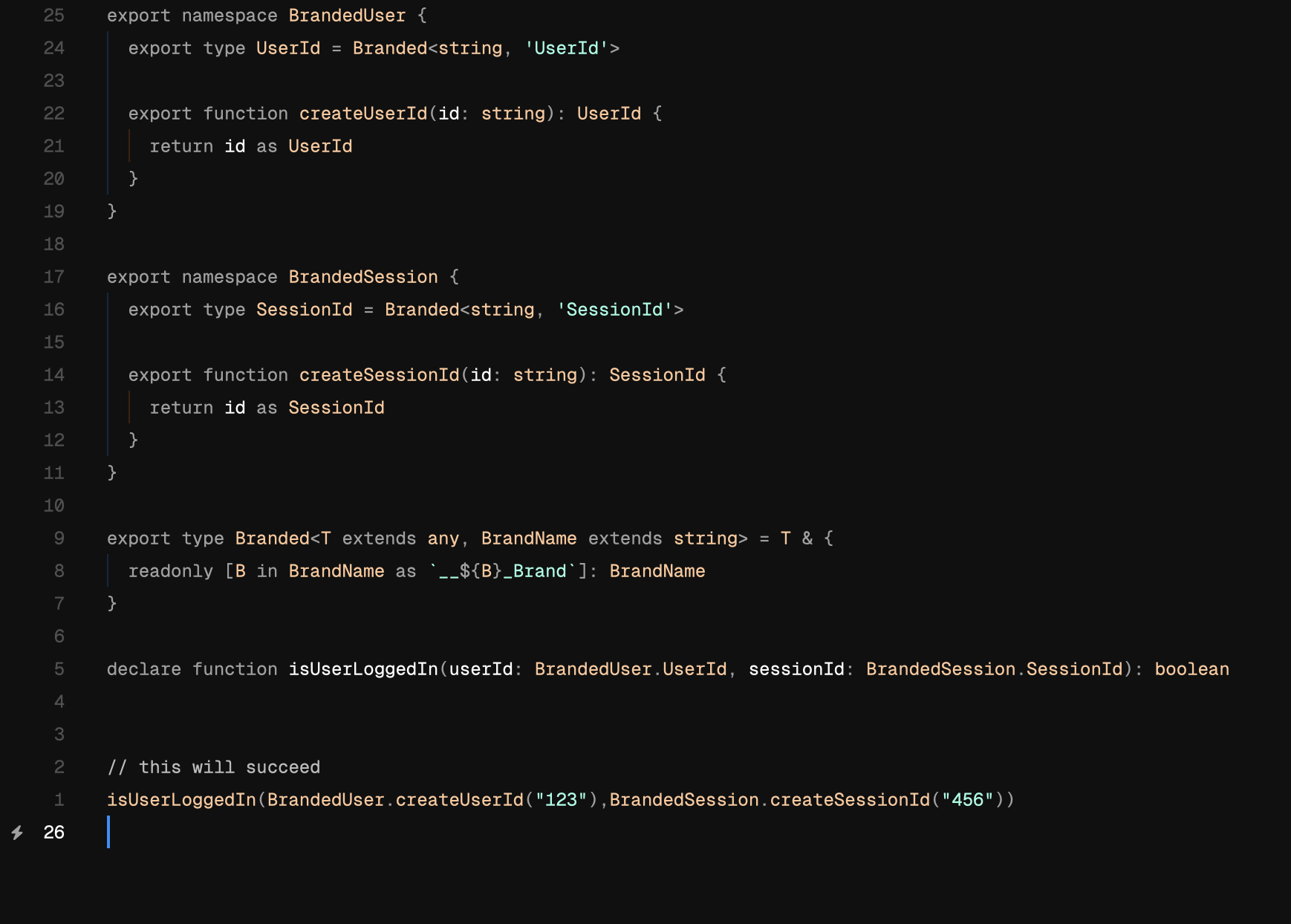

declare function isUserLoggedIn(userId: BrandedUser.UserId, sessionId: BrandedSession.SessionId): boolean

isUserLoggedIn(BrandedSession.createSessionId('session-id'), BrandedUser.createUserId('user-id'))Now when we pass the UserId and SessionId to the isUserLoggedIn function, Typescript will check that the types are correct.

- When we pass normal primitive types to the function, Typescript will give an error, as it expects

UserIdandSessionIdtypes and these types are narrower thanstringtype.

- When we pass the branded types to the function but in reverse order, Typescript will give an error, as it expects

UserIdandSessionIdtypes in the correct order.

- When we pass the branded types to the function in the correct order, Typescript will not give an error, as it expects

UserIdandSessionIdtypes in the correct order.

Extra: Branded types with runtime checks using effect-ts

Effect Ts is a library that provides a functional programming API for building applications in Typescript. It provides a lot of utilities for working with types in a functional way. One of the utilities it provides is for the Branded type, which is similar to the branded type we created earlier. The Branded type in effect-ts provides runtime checks to ensure that the branded type is used correctly. (https://effect.website/)

import { Brand } from "effect";

/**

* Branded types are TypeScript types with an added

* type tag that helps prevent accidental usage of

* a value in the wrong context. They allow us to create

* distinct types based on an existing underlying type,

* enabling type safety and better code organization.

*/

export type UserId = string & Brand.Brand<"UserId">;

export const UserId = Brand.nominal<UserId>();

export type SessionId = string & Brand.Brand<"SessionId">;

export const SessionId = Brand.nominal<SessionId>();

declare function isUserLoggedIn(userId: UserId, sessionId: SessionId): boolean;

isUserLoggedIn(UserId("user-id"),SessionId("session-id"));Do checkout effect-ts as it is a great library for building robust and type-safe applications in Typescript.

Everyone’s favorite Zesty Zod also provides a way to create branded types with runtime checks. (https://zod.dev/?id=brand)

Conclusion

- If you work a lot with

Ids, then in my opinion, you will benefit a lot from Branded types. You will be able to raise possible runtime and logic errors at compile time and make code more readable by replacing general-purpose types with more domain-specific ones. - With only a few helper functions, they can be easy to use and give you more confidence in your code.

- Personally, for me, it helped me understand Typescript better and how to use it to make my code more robust and maintainable.